She Thinks, Therefore She Can

Doubt Makes You Think — Cogito Ergo Sum — The Cartesian Presupposition

She Thinks, Therefore She Can

A woman with a mind is fit for any task.

— Christine de Pizan (1364-1440)

It is better to be feared than loved, if you cannot be both.

— Niccolò Machiavelli (1469-1527)

God writes the Gospel not in the Bible alone, but also on trees, and in the flowers and clouds and stars.

— Martin Luther (1483-1546)

Cogito ergo sum. (I think; therefore, I am.)

— René Descartes (1596-1650)

There is a God-shaped vacuum in the heart of every man which cannot be filled by any created thing, but only by God, the Creator, made known through Jesus.

— Blaise Pascal (1623-1662)

Judge of a man by his questions rather than by his answers.

— Voltaire (1694-1778)

If my soldiers were to begin to think, not one of them would remain in the army.

— Frederick the Great (1712-1786)

That all our knowledge begins with experience there can be no doubt.

— Immanuel Kant (1724-1804)

There are no facts, only interpretations.

— Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900)

The self is not something ready-made, but something in continuous formation through choice of action.

— John Dewey (1859-1952)

A man is nothing but the product of his thoughts; what he thinks, he becomes.

— Mahatma Gandhi (1869-1948)

The most thought-provoking thing in our thought-provoking time is that we are still not thinking.

— Martin Heidegger (1889-1976)

We have now sunk to a depth at which restatement of the obvious is the first duty of intelligent men.

— George Orwell (1903-1950)

I believe that a work of art, like metaphors in language, can ask the most serious, difficult questions in a way which really makes the readers answer for themselves; that the work of art far more than an essay or tract involves the reader, challenges him directly and brings him into the argument.

— George Steiner (1929-2020)

Women cannot complain about men anymore until they start getting better taste in them.

— Bill Maher (1956-)

Sophia’s library was a riot of parchment and possibilities, the walls lined with the musings of ancients and the conjectures of contemporaries. It was here, in this chamber of thought and sanctuary of study, that Sophia waged her quiet rebellion against the confines of convention. She found solace in the words of Christine de Pizan, a pioneer who, centuries before, dared to assert the capabilities of a woman's intellect in a world that preferred it silent.

A woman with a mind is fit for any task.

— Christine de Pizan (1364-1440)

These words were more than mere text to Sophia; they were the very sinew that connected her aspirations to her actions, the affirmation she required when the shadows of doubt crept in through the tall windows of her study. She’d mutter the phrase under her breath, a silent incantation to stir her spirits whenever the candlelight flickered and the loneliness of her scholarly pursuit threatened to engulf her.

The town outside her window bustled with the usual commerce and chatter, a world that spun on the axis of routine and remained oblivious to the revolutions that churned in Sophia’s head. Her thoughts often drifted to the artisans, the craftsmen, the mothers who haggled in the markets, women who possessed minds as sharp and capable as any man’s, yet were relegated to roles that seldom scratched the surface of their potential.

With each passing day, Sophia became more convinced that the scope of what one could achieve was not preordained by birth or gender but by the tenacity of one’s spirit and the vigor of one’s mind. She would host salons, much to the chagrin of her critics, where ideas were the currency and intellect the only measure of worth. These gatherings, though scoffed at by some, began to draw the attention of forward-thinkers and, reluctantly, even those who once dismissed her.

Sophia’s wit was sharp, her tongue even sharper, and her humor a blend of whimsy and wisdom. She could invoke laughter with a clever turn of phrase or provoke thought with a pointed question, ensuring her company was both enlightening and entertaining.

Her laughter, bright and unguarded, would often echo down the corridors, a testament to the joy she found in her pursuit. She believed that enlightenment did not necessitate solemnity; rather, it could—and should—be accompanied by the levity of a heart unburdened by ignorance.

With each evening’s end, when the guests had left and the quiet settled like dust upon the room, Sophia would return to her desk. Here, in the solitude, she would pen her own contributions to the canon of human thought. It was her hand that would inscribe the questions and her mind that would divine the answers. In the silence, she composed arguments and counterarguments, exploring the vast landscapes of philosophy, science, and society.

Her name, she knew, would be whispered in the annals of history not as a footnote but as a chapter—a testament to the power of a thinking woman who turned the tide of her own destiny with nothing but the force of her intellect and the courage of her convictions.

As the new day dawned, Sophia found herself in the midst of her thriving garden, an emerald kingdom where the fruits of her labor grew alongside her burgeoning thoughts. It was here, amidst the flora and fauna, that she often contemplated the complexities of power and affection—a duality that was as delicate as the petals of roses and as dangerous as the thorns that guarded them.

It is better to be feared than loved, if you cannot be both.

— Niccolò Machiavelli (1469-1527)

The words of Machiavelli, often misinterpreted as the musings of a cold-hearted strategist, resonated with Sophia in a different tone. She considered them not with malice but as a practical guide to navigating the treacherous waters of human relationships, especially for a woman who had carved out a place in the dominion of the learned.

She had experienced the sting of envy and the warm embrace of admiration, sometimes from the same colleagues within the span of a single discourse. Her intellect could command the room, her insight could change the course of a debate, and thus, she knew the weight of respect and the hollowness of hollow affections.

Alexander, the town's most esteemed academic and Sophia's occasional sparring partner in debates, often joked with her about the Machiavellian balance she maintained.

"If they love you for your mind, Sophia, they'll respect you. If they fear your wit, they'll never dare underestimate you," he'd say, his laughter a baritone rumble that harmonized with her soprano chuckles.

Their banter was the highlight of the salons, where jest and genius intermingled freely. Sophia’s influence grew, not through intimidation but through the undeniable force of her intellect and the evident integrity of her character. She did not seek to be feared; rather, she found that being underestimated provided her with the advantage of surprise—a weapon she wielded with surgical precision.

Yet, in the quiet moments, as she tended to her roses, Sophia questioned the premise of Machiavelli's counsel. Was it truly better to be feared? Or was there a strength in being loved that fear could never replicate? She pondered over this as she pruned the bushes, the fragrance of the blooms a sweet counterpoint to the sharpness of her thoughts.

It was during one such contemplative afternoon that Alexander visited her garden, a rare occasion where the lines of public spectacle and private friendship blurred. They spoke of many things—politics, philosophy, and the peculiarities of the human heart.

"It’s easy to govern with fear," Alexander mused, plucking a wayward leaf from a vine, "but to lead with love, to inspire loyalty that's not born of dread—that's the true challenge."

Sophia nodded, her gaze following the flight of a butterfly, a creature delicate yet free, loved by the garden flowers, not feared.

"A ruler might command the hand, but only a leader can win the heart," she replied, her words a whisper that carried the weight of conviction.

Their discourse meandered like the garden paths, leading them to truths often overlooked. And as the shadows grew long and the sunlight waned, Sophia and Alexander found themselves in accord, their minds meeting at the crossroads of power and affection, fear and love, with the understanding that the heart, much like the garden, could not be compelled, only nurtured.

Sophia's garden was not merely a retreat from the lively debates and erudite musings of her salon; it was also a sanctuary where she could ponder the divine. The intricate dance of the cosmos and the natural world spoke to her of a grandeur beyond the reach of human contrivance, a symphony composed by an unseen maestro.

God writes the Gospel not in the Bible alone, but also on trees, and in the flowers and clouds and stars.

— Martin Luther (1483-1546)

She would recite these words of Martin Luther as if they were a hymn, each syllable a note that soared high above the timberline of her earthly garden.

It was a sun-dappled afternoon when Alexander found Sophia in her arboreal chapel, her hands not in the soil but folded in reflection beneath the boughs of an ancient oak. They often debated the existence of the divine, Alexander the skeptic, Sophia the seeker, and it was here they would continue their endless, amiable contest of beliefs.

"Sophia, you see the hand of God in nature, and I see the beauty of chance and chaos," Alexander quipped, yet his voice held a note of reverence, touched by the tranquility of the grove.

She smiled at him, her eyes reflecting the canopy's mosaic of light and shadow. "Perhaps," she mused, "the divine is in the details, the order in the chaos, the grand design woven into the tapestry of existence."

Their conversations on faith were never fraught with tension but filled with the joy of discovery. Sophia believed that if there was a divine author, their creation was not limited to the scriptures but was an ongoing narrative written in the living world, one in which every creature, every leaf, and every cloud was a word, a sentence, a parable.

The garden was a place of epiphany for Sophia, a living text that she read with a reverent curiosity. Alexander, while not sharing her certainty, could not deny the sense of wonder that the natural world inspired. In the presence of such complexity and majesty, his skepticism softened, and he found himself considering possibilities that his rational mind would otherwise dismiss.

They spent hours beneath the oak, their dialogue a delicate weaving of theology and philosophy, where even the skeptic found solace in the possibility of a grander plan and the believer found the courage to question.

As the day waned and the stars began to punctuate the evening sky, they lay on the grass, the dome of heaven an ancient parchment inscribed with celestial prose. Sophia pointed to the constellations, tracing the narratives that had been told and retold across cultures and centuries.

"The stars," she whispered, "are the text from which we derive not only knowledge but wisdom. They are the legacy of God's breath upon the canvas of the universe."

Alexander watched her, the fervor in her words illuminating her in the twilight as if she were part of the cosmic story she so cherished. In her eyes, he saw the reflection of the starlit sky and, for a moment, he felt the profound connection between the heavens and the earth—a tapestry of existence where, perhaps, every living thing was intertwined.

In the starry quietude, both scholar and skeptic found a shared reverence for the mystery and beauty of life, a sacred scripture where every leaf, every cloud, and every star was a testament to the sublime.

As the night deepened, their discussion transcended into a comfortable silence, allowing the whispers of the divine, as interpreted by Sophia's faith and Alexander's wonder, to speak for itself.

The night sky had deepened to the richest of blues, a velvet backdrop pierced by the light of countless stars, as Sophia and Alexander retired from the garden to the warmth of her study. Here, amidst the clutter of quills and parchment, the air still buzzed with their earlier musings on divinity and nature. They found themselves circling back to the essence of consciousness, to the core of their own being, a topic that invariably led them to the words of René Descartes.

Cogito ergo sum. (I think; therefore, I am.)

— René Descartes (1596-1650)

The statement hung in the air, as potent as the scent of ink and parchment that permeated the room.

For Sophia, these words were not just the foundation of modern philosophy but the anchor of her own existence. They were the strokes of clarity amidst the fog of uncertainty, the irrefutable truth that emerged when all else was questioned.

"Consider this, Alexander," Sophia began, her eyes alight with the fire of intellectual fervor, "our thoughts are the only proof of our existence. Without them, we are but phantoms in a world of shadows."

Alexander, ever the pragmatist, chuckled at her passion yet nodded in agreement. "Our existence is validated by our awareness, by our ability to think and to doubt," he conceded, tapping a finger thoughtfully against his chin.

Their conversation spiraled into the wee hours, turning from the nature of existence to the existence of nature and the myriad ways in which thought shaped reality. Sophia, with a mischievous glint in her eye, posed a challenge to Alexander, one that echoed the playful debates of their salons.

"Imagine, my dear skeptic, that every thought we think alters the reality around us, a constant act of creation and re-creation. Where then does that leave us? Are we gods of our own universes, masters of our fates through the sheer power of thought?"

Alexander responded with a mock groan, though his eyes danced with delight at the game. "If that were true, Sophia, then every foolish thought I've entertained would have wrought havoc by now!"

Laughter filled the room, a testament to the joy they found in their philosophical sparrings. Yet, beneath the humor, there was a profound respect for the magnitude of Descartes' proclamation. They understood that to think was to engage with the world, to question was to connect with the fabric of existence.

As dawn's first light began to seep through the curtains, painting the room with hues of gold and amber, Sophia and Alexander sat in contemplative silence, each lost in thought. In those quiet moments, as the world slowly awakened, they recognized the profound power of their own consciousness, the undeniable reality of their existence affirmed with each idea conceived, each question posed.

The conversation eventually wound down, as all things must, with a tacit acknowledgment of the depth they had traversed. They parted with a sense of wonder at the resilience of the human spirit and the boundless realms of the mind, a shared journey into the heart of what it means to be.

In the aftermath of their exhaustive night, Sophia found herself alone, enveloped in the serene silence that followed Alexander's departure. The soft light of dawn drew her to the window, where she watched the world awaken. Her mind, usually so teeming with thoughts, turned contemplative, reflecting inward.

There is a God-shaped vacuum in the heart of every man which cannot be filled by any created thing, but only by God, the Creator, made known through Jesus.

— Blaise Pascal (1623-1662)

Sophia pondered Pascal’s words, feeling their weight and their truth resonating within her.

She had always felt that void, that inexorable pull toward something greater than herself, something beyond the empirical world she so loved. It was a space of longing, of yearning for a connection that transcended the physical, a search for meaning in the vast tapestry of existence.

As the morning light grew stronger, casting patterns on the floor, Sophia’s contemplation was interrupted by a ruckus outside. Peering down, she noticed a gathering of townspeople in the square, their faces animated with what appeared to be a mixture of excitement and apprehension.

Curiosity piqued, she donned her cloak and descended into the throng. The cause of the commotion was soon apparent; a troupe of actors had arrived, their colorful wagon unfolding into a makeshift stage. Their leader, a man with a booming voice and a flamboyant hat, proclaimed they would perform a play about the life of Jesus, promising a tale of love, sacrifice, and redemption.

The play, as promised, was a vivid tableau of human emotions, a narrative rich with allegory and metaphor. Sophia found herself moved by the performance, by the actors’ portrayal of faith and doubt, of love and loss. It was a stark reminder of the vacuum Pascal had described, the innate human desire to fill the void within with something, or someone, profound.

As the final act closed, the troupe invited the audience to share their thoughts. The invitation sparked a lively discussion among the townspeople, with Sophia listening intently. She was fascinated by the diversity of interpretations, by the myriad ways in which the play resonated with each individual.

"It seems," she mused aloud, "that the vacuum Pascal speaks of is not a singular void but a collection of spaces within us, each yearning to be filled with our own unique understanding of the divine."

The actors were intrigued by this thoughtful spectator, and their leader, a man of keen intellect himself, approached her.

“Your words suggest you are familiar with the feeling of emptiness,” he said, his gaze inquisitive.

Sophia nodded. "I believe we all are, to some degree. It is a space that knowledge can enrich but not entirely fill, a chamber in our hearts that perhaps only faith can fully occupy."

Their conversation unfolded like the petals of a blooming rose, each layer revealing new depths, new nuances to the human experience. Sophia found herself engaging with the actors, sharing insights and drawing laughter and solemn nods in equal measure.

As the day waned and the actors prepared to depart, Sophia returned to her home, her mind alight with new considerations. Pascal's vacuum, she understood, was more than a mere absence—it was a space of potential, a wellspring for growth, reflection, and ultimately, for finding one's own connection to the infinite.

The questions of faith and fulfillment would continue to accompany her, as ever-present companions in her journey through thought and belief.

The encounter with the actors and their portrayal of spiritual questing lingered with Sophia well into the evening, sparking a renewed vigor in her intellectual pursuits. As the sun dipped below the horizon, she found herself back in her study, surrounded by the comforting presence of her books and the ever-persistent hum of her thoughts.

Judge of a man by his questions rather than by his answers.

— Voltaire (1694-1778)

Sophia echoed Voltaire's sentiment with a thoughtful nod, considering how this approach had always been central to her dialogues and debates.

The philosophy of Voltaire had often provided a spice to Sophia's scholarly repasts, and tonight, it flavored her musings with a particularly sharp tang. It wasn't the answers she had offered to the troupe's inquiries that gratified her but the quality and depth of the questions they had posed in return. They reflected a curiosity and a zest for understanding that outshone the rote responses of the dogmatic.

With a wry smile, she recalled a recent exchange with Alexander. His query about the nature of belief had not sought to elicit a simple reply but had invited her to explore the landscape of her own convictions. It was a clever way of prompting introspection and self-discovery, a method she greatly appreciated.

The room was quiet, but her mind was anything but. She imagined hosting a new salon, one centered around questions rather than themes, where the merit of a person would be measured by the curiosity they exhibited rather than the conclusions they proclaimed.

Sophia’s reverie was interrupted by a soft knock at the door. It was Alexander, who entered with a sheepish grin, an unspoken apology for the late intrusion hanging in the air between them.

"Sophia, I come bearing a question that has been plaguing me since our last encounter," he began, his eyes twinkling with a mix of challenge and charm.

She raised an eyebrow in mock severity. "Then, sir, you must be judged accordingly."

They laughed, a comfortable sound that filled the room with warmth. The exchange of questions that night was like a dance, each step leading further into a maze of thoughts and revelations. It was a testament to the wisdom of Voltaire's words, for each query revealed more about the questioner than any direct statement of fact ever could.

As they delved into the night, Sophia and Alexander discovered layers of understanding about the world and each other that had previously eluded them. It was a delightful unraveling of preconceptions, a shedding of biases that left them both feeling surprisingly liberated.

By the time the candle had burned down to a stub, they had traversed topics ranging from the philosophical to the trivial, each treated with the same level of earnestness and wit. In this exchange of inquiries, they recognized a shared desire to learn, to grow, and to connect more deeply with the world around them.

The night ended with a newfound appreciation for the art of questioning and the bonds it could forge. Sophia, reflecting on Voltaire's insight, understood that it was not the certainty of answers that enriched one's life, but the pursuit encapsulated in the questions themselves.

In the glow of the new day, Sophia found Alexander waiting for her in the garden. His presence was a pleasant surprise, as their nocturnal dialogues were seldom followed by such immediate sequels. Alexander was pacing by the fountain, hands clasped behind his back, lost in thought.

If my soldiers were to begin to think, not one of them would remain in the army.

— Frederick the Great (1712-1786)

The line was delivered with a wry inflection, as if the ghosts of Frederick the Great’s soldiers marched between the rose bushes and lavender.

Sophia laughed, the sound mingling with the morning chorus of the birds. "Are you suggesting, Alexander, that thought is the enemy of duty?"

He stopped his pacing and turned to her, a spark in his eyes. "On the contrary, I believe thought enhances duty. It is the unthinking obedience that troubles me."

Their conversation meandered through the philosophical battlefield where duty met volition. Alexander recounted tales from his military ancestors, men who served kings and causes without question, and Sophia countered with stories of philosophers who questioned every king and cause.

The sun climbed higher, and the garden became a vibrant tapestry of light and shadow. Their debate took on a playful tone, Sophia asserting that if thinkers made poor soldiers in the field, they were the generals of progress in the realm of ideas.

"It's not the absence of thought that should be feared," Sophia said, her finger tracing the rim of a sundial, "but the refusal to act upon it."

Alexander nodded, conceding the point. "Perhaps it's a question of balance. We need the thinkers to question why we fight and the soldiers to protect our right to do so."

Their exchange was a delicate dance around the nature of service and the responsibility of the individual within society. It echoed the duality of their characters—Sophia, with her relentless questioning of societal norms, and Alexander, who valued the structure within which freedom and order coexisted.

As noon approached, their dialogue softened into comfortable silence. They had explored the notions of duty and thought, only to find themselves in a garden where both existed in harmony—the duty of the bees to their hives, the thoughtfulness of the gardener in their planting.

That all our knowledge begins with experience there can be no doubt.

— Immanuel Kant (1724-1804)

Sophia’s belief that contemplation and action were not mutually exclusive but rather complementary forces was strengthened by the morning's discourse. And Alexander found solace in the idea that his lineage of soldiers were not just pawns in historical battles but individuals who, in their own ways, contributed to the narrative of their time.

As they parted ways, the echo of Frederick the Great’s words lingered, a reminder that while thought could unsettle, it was also the catalyst for growth, the precursor to action, and the mark of true service to one’s own ideals.

The season had turned, bringing with it the crispness of autumn that painted the leaves in fiery hues and filled the air with the earthy scent of change. Sophia sat at her favorite spot by the hearth, a tome of Immanuel Kant in her lap, but her thoughts were adrift, untethered by the philosopher's rigorous treatises on experience and perception.

It was Nietzsche's aphorism that had captured her mind, fluttering through her consciousness like a stubborn leaf caught in a gust of wind.

There are no facts, only interpretations.

— Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900)

The words seemed to mock the certainty of the world outside her window, where the trees stood as solid testimonies to the existence of a reality that one could touch, smell, and see.

Sophia mused on this, considering how the vibrant red of a maple leaf could be a simple matter of biology to one person and a symbol of profound beauty to another. It was the latter—a reality colored by the mind's eye—that gave the leaf its poetry and its power.

Alexander arrived as she pondered this, his presence heralded by the brisk knock that had become a familiar prelude to their discussions. With a flourish, he presented her with a maple leaf, its color a perfect echo of the one in her musings.

"Beautiful, isn't it? But is its beauty a fact, or is it our interpretation?" he asked, echoing her internal dialogue.

Sophia held the leaf up to the light, watching the veins like paths in a miniature world. "Nietzsche would argue the latter," she replied, "and today, I am inclined to agree with him."

Their conversation turned to the essence of reality, to the ways in which human consciousness painted the world with subjective strokes. They spoke of the sciences and the arts, of the empirical and the emotional, and how each discipline sought to understand the world through its own lens.

"The leaf is not just a leaf," Sophia said, her eyes reflecting the dancing flames. "It's a repository of meaning, a vessel for our thoughts and experiences."

Alexander smiled, his skepticism always tempered by his fondness for Sophia's romantic view of the world. "Then perhaps our entire reality is but a canvas for our interpretations."

The evening waned as they explored this notion, the hearth's glow a gentle sentinel to their discourse. Sophia argued that while facts were the bones of truth, interpretation was its flesh and blood, giving it life and relevance.

As the fire burned down to embers, Sophia and Alexander found themselves in a realm of philosophy where the tangible met the abstract, where Nietzsche's words cast long shadows over the certainties they held. The conversation left them with more questions than answers, a testament to the philosopher's enduring challenge to the very fabric of understanding.

With the leaf as a token of their dialogue, they parted, the world outside her study a tapestry woven from the countless threads of perception and interpretation, richer for its complexities and contradictions.

The debate with Alexander over Nietzsche's assertion of interpretation over fact lingered in Sophia's mind long after the embers of their discussion had cooled. It was a seed that germinated slowly, branching out into myriad avenues of thought, each more intriguing than the last. Her intellectual wanderings were soon accompanied by the pragmatism of John Dewey, whose philosophy seemed to weave itself seamlessly into the fabric of her contemplations.

The self is not something ready-made, but something in continuous formation through choice of action.

— John Dewey (1859-1952)

This notion struck a chord with Sophia, resonating with the vibrancy of a plucked string. It was a melody that harmonized with her own beliefs, a counterpoint to the existential ponderings that Nietzsche had inspired.

The idea that one's identity was not a static entity but a dynamic construct shaped by decisions and experiences was liberating. Sophia found herself reflecting on her journey, on the myriad decisions that had led her to this point in her life. Each book she had devoured, every salon she had hosted, and all the debates she had engaged in with Alexander were not just milestones but sculptors of her being.

She decided to bring this topic to their next meeting, curious to see how Alexander would respond to Dewey's perspective. When he arrived, she greeted him with the question, "Do you believe you are the same person who first knocked on my door, Alexander?"

He paused, taken aback by the suddenness of the inquiry but intrigued by its depth. "I suppose not," he mused after a moment. "Each conversation, each argument, has chiseled away at me, shaping me into the person before you today."

Their discussion that evening revolved around Dewey's idea, exploring the concept of the self as a work in progress. They debated the implications of this perspective on personal responsibility, ethics, and societal roles. Sophia argued that recognizing the self as malleable empowered individuals to become architects of their own destinies, rather than mere products of circumstance.

Alexander, ever the foil to Sophia's enthusiasm, raised questions about the limits of self-formation. "Is there a core to our being," he wondered, "or are we simply the sum of our experiences?"

Sophia leaned forward, her eyes alight with the challenge. "Perhaps our core is our capacity for change, our potential to evolve with each new experience."

The night deepened around them, the conversation ebbing and flowing like the tide. They found themselves returning to the idea of interpretation, now viewed through the lens of personal development. Just as they interpreted the world around them, they also interpreted themselves, each experience a brushstroke on the canvas of their identities.

As Alexander left, Sophia felt a profound sense of gratitude for their friendship. It was a catalyst for growth, a mirror reflecting her own thoughts back at her in ways that challenged and enriched her understanding of herself.

The dialogue with Alexander, inspired by Dewey's pragmatism, had not only deepened Sophia's appreciation for the fluid nature of identity but had also reinforced her belief in the transformative power of intellectual engagement.

In the weeks that followed their exploration of Dewey’s pragmatism, Sophia found herself increasingly drawn to the contemplation of action and its relationship with the self. It was during this period of introspection that she encountered the words of Mahatma Gandhi, which seemed to echo her own evolving thoughts on the matter.

A man is nothing but the product of his thoughts; what he thinks, he becomes.

— Mahatma Gandhi (1869-1948)

This statement, profound in its simplicity, struck Sophia with the force of revelation. It was as if Gandhi had distilled the essence of her recent discussions with Alexander into a single, unassailable truth.

Sophia recognized in Gandhi's words a synergy with Dewey's philosophy of the self in continuous formation, but with an emphasis on the moral and ethical dimensions of thought. The idea that one’s very being was shaped by the quality and nature of one’s thoughts prompted Sophia to reassess her own patterns of thinking and the actions they inspired.

When Alexander next visited, Sophia was eager to share Gandhi’s insight with him, to gauge his reaction and to delve into the implications of such a philosophy. She presented the quote as a challenge, a gauntlet thrown down between them to explore the depths of their own convictions.

Alexander accepted the challenge with his usual blend of skepticism and curiosity. "So, our thoughts dictate our reality, shape who we are and who we become? It's a potent idea but also a daunting responsibility."

Their conversation spiraled out from this point, touching on the nature of thought itself, the power of positive versus negative thinking, and the responsibility that came with such creative power. They debated whether thoughts had an inherent ethical dimension or if morality was imposed upon them by societal norms and individual conscience.

Sophia argued that thoughts, while initially free from moral judgment, become imbued with ethical weight through the choices they lead to. "Our actions are the truest expression of our thoughts," she posited. "In choosing our actions, we choose who we become, guided by our moral compass."

Alexander countered, pondering the influence of external factors on thought and action. "But how free are we in choosing our thoughts? Are they not shaped by our environment, our experiences, and our desires?"

The discussion that night was animated, with Sophia and Alexander traversing the philosophical landscape from determinism to free will, from the personal to the universal. It was a testament to their friendship that such discussions, while heated, only served to deepen their respect and affection for each other.

As the evening drew to a close, Sophia felt a sense of fulfillment, a recognition that their dialogue was a living embodiment of Gandhi's philosophy. Through their exchange of ideas, through the very act of thinking deeply and critically about their beliefs, they were in a constant state of becoming, shaping themselves and each other in the process.

Sophia was left with a profound sense of the power of thought, not just as a tool for understanding the world, but as the very substance of her being. It was a realization that would guide her actions henceforth, a beacon illuminating the path of her personal evolution.

As autumn deepened, its colors burning into the world with the intensity of a setting sun, Sophia found herself wrestling with a restlessness of spirit. This disquiet was not born of discontent but of a yearning for deeper understanding, a desire to grasp the elusive essence of being that seemed to dance just beyond her intellectual reach.

It was in this state of introspective questing that she stumbled upon the words of Martin Heidegger, words that seemed to crystallize the nebulous thoughts that had been swirling through her mind.

The most thought-provoking thing in our thought-provoking time is that we are still not thinking.

— Martin Heidegger (1889-1976)

The statement struck Sophia like a thunderclap, reverberating through the chambers of her soul with its audacious challenge.

To Sophia, Heidegger’s pronouncement was not a condemnation but a call to arms, an invitation to engage with thought at a level she had never considered. It prompted her to question the very nature of thinking itself. Was it merely the processing of information, the mechanical act of the mind organizing and analyzing data? Or was there something more, a deeper, more profound engagement with the essence of reality?

When Alexander arrived for their regular meeting, he found Sophia in a state of animated contemplation, her eyes alight with the fire of intellectual discovery.

"Alexander," she began without preamble, "Heidegger challenges us. He asserts that despite our age being one of unprecedented knowledge and information, we have yet to truly engage with thinking. What do you make of that?"

Alexander, taken aback by her intensity, took a moment to reflect before responding. "Perhaps he's suggesting that true thinking involves more than just the accumulation of facts. That it requires a deeper engagement with the questions that those facts present."

Their discussion that evening took on a philosophical depth that surpassed their previous encounters. Sophia and Alexander delved into the nature of thought, exploring its relationship with being, with the essence of what it means to exist. They pondered the difference between thinking and understanding, between knowing and comprehending.

Sophia proposed that true thinking was akin to a dialogue with the world, a conversation not just with the what of things but with the why and the how. "It's not enough to know," she said. "We must understand, we must relate, we must connect."

Alexander, inspired by Sophia's insight, suggested that perhaps this was what Heidegger meant by being truly thoughtful. "To think," he said, "is to dwell within the question, to live the mystery of being rather than merely to seek answers."

As the night wore on, their conversation became a meditation on the nature of existence, a journey through the landscape of thought that left them both exhilarated and humbled. They realized that to engage with thinking in the way Heidegger described was to embrace the unknown, to find comfort in uncertainty, and to see in every question a pathway to deeper understanding.

Sophia and Alexander parted ways that night with a sense of awe at the vastness of the intellectual terrain they had yet to explore. They understood that the journey of thought was endless, that each answer unearthed new questions, and that in this perpetual questing lay the true essence of being.

The encounter with Heidegger’s challenge had transformed their understanding of thinking, imbuing their intellectual pursuits with a new depth and a renewed sense of purpose.

As we draw close to the culmination of Sophia and Alexander’s philosophical explorations, let us consider the pragmatic wisdom of George Orwell, who reminds us of the importance of stating the obvious in times of obfuscation.

The seasons cycled through their eternal dance, and winter's cloak settled upon the world, muffling its sounds and softening its edges with snow. Within this hushed tranquility, Sophia found herself reflecting on the journey of thought she had embarked upon with Alexander. Their conversations had meandered through the minds of philosophers and poets, each encounter leaving an indelible mark on their understanding of the world and their place within it.

It was during one of these reflective moments that Sophia encountered a statement by George Orwell that struck a chord with her, resonating with the clarity and precision of a bell in the silent winter air.

We have now sunk to a depth at which restatement of the obvious is the first duty of intelligent men.

— George Orwell (1903-1950)

The stark truth of Orwell's observation was undeniable, a beacon of light in an era increasingly muddied by the deliberate obfuscation of facts and the manipulation of truth.

Sophia recognized the wisdom in Orwell’s admonition, understanding that in a time when truth could be so easily bent and reshaped by those with nefarious intent, the act of stating the obvious, of clinging to the fundamental truths that bind humanity, was itself a radical act.

When Alexander next visited, Sophia greeted him with Orwell’s quote, presenting it as the foundation for their discussion. "In an age where truth is a battleground," she posited, "our obligation is to reaffirm the undeniable, to champion what is clear and self-evident."

Alexander nodded, his expression grave. "The distortion of truth isn’t just a philosophical concern; it’s a societal crisis. The manipulation of facts threatens the very fabric of our democracy, our ability to make informed decisions, and our understanding of reality itself."

Their conversation that evening was less an exploration of philosophical nuances and more a dissection of the current state of discourse, an examination of the mechanisms by which truth was twisted and obscured. They debated the role of the intellectual, the responsibility of those who sought to understand the world not just to uncover new truths but to defend the old ones, those self-evident truths upon which the integrity of thought itself rested.

Sophia argued that the act of thinking, of truly engaging with the world in the manner Heidegger described, was incompatible with the acceptance of untruth. "To think," she said, "is to seek truth, even — and especially — when it is obscured by layers of falsehood."

Alexander, ever the pragmatist, wondered about the efficacy of their efforts. "But can we, as individuals, make a difference? Can the restatement of the obvious turn the tide against a deluge of disinformation?"

Sophia’s response was measured but firm. "Perhaps not alone. But each voice that joins in the chorus strengthens it, makes it harder to ignore. We must believe in the power of truth, in the cumulative effect of many small acts of intellectual integrity."

As the night drew to a close, Sophia and Alexander understood that their journey of thought was not just an intellectual exercise but a moral imperative. In a world where the very concept of truth was under siege, their commitment to clarity, to the restatement of the obvious, was their contribution to the battle.

Their discussions had led them from the lofty realms of metaphysics to the pressing issues of the day, demonstrating the relevance of philosophical thought to the challenges of the contemporary world. They parted ways with a renewed sense of purpose, understanding that the defense of truth was not just the duty of the intellectual but the responsibility of every thoughtful individual.

As Sophia watched the snowflakes drift past her window, each one a unique assertion of nature's complexity, she was reminded of the importance of her own voice in the chorus of humanity, a voice that, no matter how small, had the power to affirm the truth and illuminate the darkness.

With the winter's end heralding the rebirth of the world in the tender greens and vibrant blooms of spring, Sophia found herself pondering the transformative power of art and metaphor in challenging and expanding the human intellect. It was during this season of renewal that she chanced upon a reflection by George Steiner that seemed to encapsulate her evolving thoughts on the matter:

I believe that a work of art, like metaphors in language, can ask the most serious, difficult questions in a way which really makes the readers answer for themselves; that the work of art far more than an essay or tract involves the reader, challenges him directly and brings him into the argument.

— George Steiner (1929-2020)

The sentiment struck a resonant chord within her, illuminating the myriad ways in which art had influenced her own journey of thought and understanding.

Sophia considered the myriad conversations with Alexander, their debates and dialogues that had woven through the philosophies of the ages, and she realized the truth in Steiner’s words. Art, in its broadest sense, had always been a silent participant in their discussions, whether through the poetry they quoted, the historical contexts they explored, or the philosophical allegories they unraveled.

With this realization, Sophia decided to curate an evening dedicated to exploring the intersection of art, metaphor, and philosophy. She invited Alexander, promising an experience that would engage both the intellect and the senses.

As Alexander stepped into Sophia's home on the appointed evening, he was greeted by an array of artworks that Sophia had carefully selected from her collection. Each piece, whether a painting, sculpture, or fragment of poetry, was accompanied by a question, a challenge to delve deeper into the themes and ideas it represented.

The evening unfolded as a journey through the landscape of human thought, guided by the silent eloquence of the artworks. Sophia and Alexander found themselves debating the nature of beauty, the complexities of human emotion, and the eternal quest for meaning, their discussion enriched and expanded by the art that surrounded them.

Sophia pointed to a particularly striking painting, its vibrant colors and abstract forms a stark departure from the classical pieces that also adorned the walls. "Consider this," she said, invoking Steiner’s perspective, "does not this work ask of us to confront our own perceptions of reality, to question what we see and why we see it as we do?"

Alexander, who had always approached art from a more analytical perspective, found himself drawn into the emotional and subjective experience the painting evoked. "It's as if the artist is challenging us to find our own truth within the chaos," he mused, echoing Steiner’s assertion that art involves the viewer in a direct and personal dialogue.

The night grew late, and as the final threads of their conversation trailed off, Sophia and Alexander were left with a profound sense of the power of art to transcend the limitations of language, to communicate the ineffable, and to inspire a deeper engagement with the world.

Sophia’s initiative had demonstrated vividly the truth of Steiner’s words, affirming that art, in its myriad forms, was not merely a reflection of human thought but a catalyst for it, a medium through which the most complex and challenging questions could be posed and explored.

As Alexander departed, both he and Sophia were reminded of the indelible role of art in the human endeavor to understand, to feel, and to connect with the ineffable mysteries of existence. Their journey through the realms of thought and philosophy had been immeasurably enriched by this foray into the world of art, a testament to the enduring power of creative expression to challenge, illuminate, and inspire.

Let's turn next to Bill Maher’s observation, a lighter yet insightful commentary on the dynamics of personal relationships and societal expectations.

Spring blossomed into summer, its warmth coaxing the world into a lush tableau of life and color. Amidst this seasonal transformation, Sophia found herself reflecting on the lighter, yet equally complex, aspects of human interaction and societal norms. It was during one such reflective moment that she recalled a statement by Bill Maher, an observation that, while seemingly flippant, offered a poignant commentary on the nature of relationships and the choices that define them.

Women cannot complain about men anymore until they start getting better taste in them.

— Bill Maher (1956-)

The quote brought a smile to Sophia's lips, not only for its humor but for the underlying truth it hinted at concerning personal responsibility and the power of choice in shaping our lives.

As she pondered Maher's words, Sophia realized that they encapsulated a broader theme that had woven itself through many of her conversations with Alexander: the theme of self-determination and the impact of our choices on our reality. Whether discussing the nature of thought and existence or the transformative power of art, the undercurrent of their dialogue had always circled back to the autonomy of the individual in crafting their destiny.

When Alexander next visited, Sophia shared Maher's quote with him, using it as a springboard to explore the lighter side of their philosophical inquiries. Their conversation meandered through the nuances of personal relationships, societal expectations, and the often humorous contradictions that defined human behavior.

Alexander, with his characteristic blend of wit and insight, offered, "Perhaps it's not just about taste but about understanding what we truly value in others. Maher's comment, while humorous, touches on the idea that our choices reflect our priorities and, ultimately, our understanding of ourselves."

Their discussion took on a playful tone as they recounted personal anecdotes and observed behaviors, highlighting the absurdities and the enlightening moments that relationships often entail. Yet, beneath the banter, there was a recognition of the serious underpinnings of Maher's observation—the idea that self-awareness and the courage to make conscious choices were fundamental to not only personal happiness but to the cultivation of meaningful connections with others.

As the evening drew to a close, Sophia and Alexander found themselves appreciating the lighter facets of their philosophical journey. Maher's quote had provided a refreshing perspective, reminding them that wisdom could be found not only in the solemn contemplations of existence but in the everyday musings on life and love.

Their journey had taken them from the profound depths of existential inquiry to the engaging complexities of social dynamics, each step enriched by the diversity of thoughts and perspectives they had explored. Sophia and Alexander parted ways that night with a renewed appreciation for the breadth of human experience, from the grandiose to the mundane, and the endless opportunities for reflection and growth that each presented.

In the end, Sophia realized that their philosophical explorations, much like the seasons, were cyclical—always returning to the core themes of thought, choice, and the pursuit of understanding, yet always with a new hue, informed by the ever-changing landscape of human knowledge and experience.

The planksip Writers' Cooperative is proud to sponsor an exciting article rewriting competition where you can win part of over $750,000 in available prize money.

Figures of Speech Collection Personified

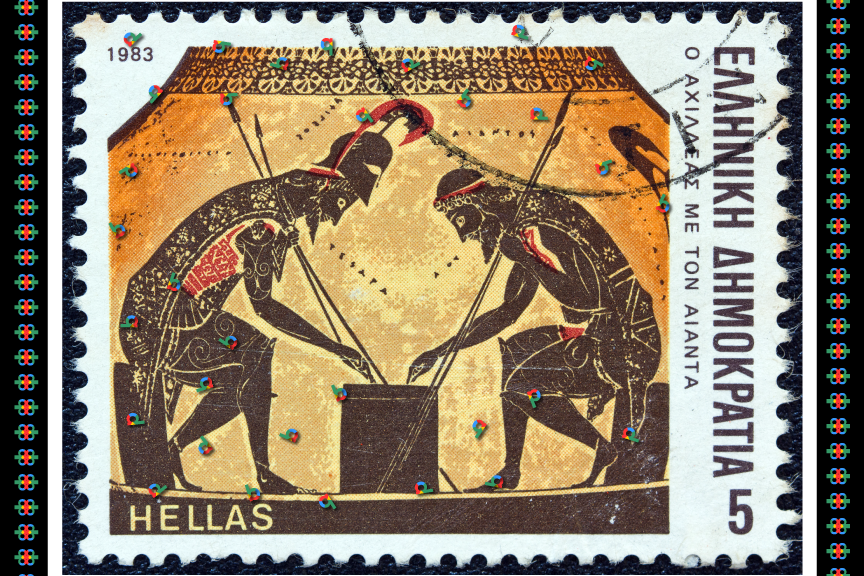

Our editorial instructions for your contest submission are simple: incorporate the quotes and imagery from the above article into your submission.

What emerges is entirely up to you!

Winners receive $500 per winning entry multiplied by the article's featured quotes. Our largest prize is $8,000 for rewriting the following article;

At planksip, we believe in changing the way people engage—at least, that's the Idea (ἰδέα). By becoming a member of our thought-provoking community, you'll have the chance to win incredible prizes and access our extensive network of media outlets, which will amplify your voice as a thought leader. Your membership truly matters!